Gojek’s Vietnam exit signals a new chapter in its battle with Grab

GoTo’s decision to leave Vietnam is rare move based on logic, and not rivalry, narrative or money—and that’s new

Welcome back,

Our plans for an article this week shifted at the last minute with news that Gojek is leaving Vietnam, its first expansion back in 2018 and a symbol of its fierce battle with Grab across Southeast Asia.

I started writing about the rivalry right at the start and find plenty of broader meaning from what might look like a logical decision from Gojek in what is a new era for the company and its rivalry with Grab.

We’ll be back on Monday with our usual weekly news recap. Until then, have a great rest of the week and weekend.

Best,

Jon

PS: Follow the Asia Tech Review LinkedIn page for updates on posts published here and interesting things that come our way. If you’re a news junkie, the ATR Telegram news feed has you covered with news as-it-happens or join the community chat here.

Grab-Gojek first era of competition comes to an end

GoTo’s decision to leave Vietnam is rare move based on logic, and not rivalry, narrative or money—and that’s new

The moment is finally here. The end of the first era of Grab-Gojek.

That might sound misguided since both companies have been public for years. Grab listed in the US in 2021 and Gojek went public on home soil in Indonesia a year later. Gojek even went through a major merger with fellow Indonesian unicorn Tokopedia just before its IPO.

Didn’t those events mark the end of an era?

You can argue the semantics but, for me, Wednesday, 4 September 2024 marked the end of this first period after—to call it correctly post Gojek-Tokopedia—left the Vietnamese market. Gojek in Vietnam marked all the negatives of that rivalry: decisions taken without logic on the basis of competing, narrative or money.

GoneViet

On the face of it, Vietnam seems like a logical choice for expansion in Southeast Asia. A population of 100 million people, half of whom are under 30, it became Gojek’s first expansion market in the heady days of August 2018 as the Indonesia firm sought to move into the gap created when Uber left the region and raise its appeal to investors.

Vietnam was the first step in an expansion that included Singapore, Thailand and the Philippines. Of those markets, only Singapore is now left.

GoTo may not be about to exit Singapore since the market has traditionally been profitable—Uber was in the black there before it left Southeast Asia—and it has a cachet attached to it. But ride-hailing is far from predictable so who is to say?

The expansion was stunted at best, or bodged if you wanted to be mean.

AirAsia acquired GET, Gojek’s business in Thailand, in a cut price deal worth $50 million in July 2021

Gojek never launched ride-hailing in the Philippines after it failed to get a permit

Coins.ph, the fintech startup Gojek acquired in the Philippines for nearly $100 million in 2019, was never integrated into the Gojek business, its product turned stagnant and it was sold to a firm run by the former CFO of Binance just two years later

Vietnam can probably be added to the list.

Initially, market share numbers suggested Gojek was giving Grab a stern test despite pitching up in Vietnam four years later—but employees at Grab often countered by claiming Gojek used to discount sprees to boost its numbers. And let’s face it, market share data is patchy at best.

Estimates vary, but Gojek Vietnam (formerly known as GoViet) is widely cited as fourth in the market with a single-digit share. That puts it, behind Grab and newer, local entrants including Xanh SM—an EV taxi service from local conglomerate Vingroup—and Be Group. GoTo itself said Vietnam, where it offers rides, food and delivery services, contributes less than 1% of all transactions.

GoTo isn’t the only international company to struggle in Vietnam: Grab stopped offering its wallet service months ago after failing to see meaningful traction and Baemin, a Korean delivery firm owned by Foodpanda parent Delivery Hero, exited Vietnam last year after four years of limited progress.

Money and war

That begs the question, why was it there in the first place?

The landscape looked very different in 2018. Gojek was locked in a battle to raise capital with Grab, and its narrative turned from dominating Indonesia—Southeast Asia’s largest economy and the world’s fourth largest population—to expanding overseas and filling that aforementioned Uber-shaped hole.

Vietnam became a way to poke the bear that was Grab. Increase promotions and discounts to increase market share and thus force Grab to make similar financial concessions, and maybe score some publicity points on the way.

It simply didn’t have the market share in Thailand or any presence in the Philippines, so Vietnam became that attack vector that forced Grab to put more focus on markets outside of Indonesia, the castle that Gojek dominated and Grab CEO Anthony Tan was so keen to take.

Tan—who is publicly a devout Christian—was so obsessed with taking top spot in Indonesia that he called it Project Jericho, named after the biblical story in which the Israelites cross into the promised land and destroy the city and all that’s in it. The walls of Jericho are said to have fallen after the Israelites marched around them for seven days. Gojek needed a way to ease the pressure on its stronghold.

On the investment side, it appeared to bear fruit. Promise of regional expansion helped Gojek become a unicorn in 2016 and then land a $2 billion round at a valuation of $9.5 billion in 2019. It even had the capital to launch its own entertainment division, which is now independent, as well as an investment firm, which has since rebranded, with GoTo being just one of its many limited partners (LPs).

The Gojek executives I spoke to at the time believed that expanding into markets already dominated by Grab, despite its head start, was still worthwhile if it helped position Gojek as a multi-market player and attract more investment, rather than remaining limited to a single market.

So while Gojek employees, and even Grab employees, may have had little faith that Gojek could establish a significant presence overseas, even in Vietnam, the company still pursued its expansion—and it may have served an important purpose.

Different needs for a different era

Fast-forward to today, though, and the situation is very different.

As a public company, Gojek has jettisoned its burdensome parts the way a spaceship releases its heavy rockets once they’ve done the job of getting out of Earth’s atmosphere and into space itself.

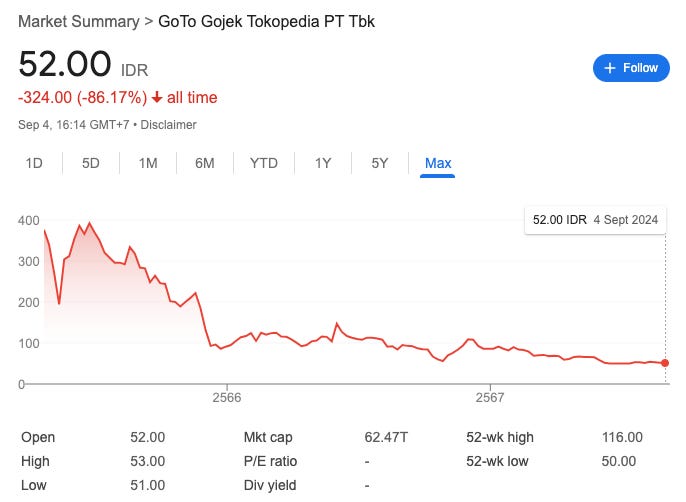

Tokopedia, its loss-making e-commerce division that had also stagnated, was sold to TikTok late last year in a multi-billion-dollar deal with fortuitous timing. Since then, GoTo has been in cost-cutting mode as it seeks a path to profitability. Its old enemy, Grab, is on the same road. While both companies have celebrated their growth with phrases like ‘adjusted positive EBITDA,’ conventional profitability remains further afield for GoTo.

Certainly, there continues to be talk of a potential merger deal—and the idea of Uber returning to Southeast Asia isn’t entirely out of the question given it has reached profitability and it still owns a chunk of Grab.

The silly games between the two have ended now, with GoTo out of Vietnam. What happens in this new era, only time will tell.

Xanh SM is effectively buying market share in Vietnam ride-hailing with artificially low prices, targeting Grab. No surprise Gojek is a casualty here.